the jinn in the machine

October 5th, 2011(learn more about the book at the “Ask Me Anything” on Reddit)

A kettle which has been just on the edge of simmering for a good long time now finally began to boil over earlier this week, as violent protests erupted in Qatif, a city in the eastern part of Saudi Arabia that like almost every city in that region of the nation is majority Shia. And like almost every other city in the Shia-dominated eastern edges of Saudi Arabia – it sits directly on top of the world’s largest remaining easily-accessible oil reserves.

Instability has been built into the region since the founding of the Saudi Kingdom, a geopolitical reality that bodes disaster for American geopolitical goals in the region. Namely, securing access to the lifeblood of Western civilization:

The Shia of Saudi Arabia, mostly concentrated in the Eastern Province, have long complained of discrimination against them by the fundamentalist Sunni Saudi monarchy. The Wahhabi variant of Islam, the dominant faith in Saudi Arabia, holds Shia to be heretics who are not real Muslims.

The US, as the main ally of Saudi Arabia, is likely to be alarmed by the spread of pro-democracy protests to the Kingdom and particularly to that part of it which contains the largest oil reserves in the world. The Saudi Shia have been angered at the crushing of the pro-democracy movement in Bahrain since March, with many protesters jailed, tortured or killed, according Western human rights organisations.

Categorizing the uprising as pro-democracy may sort of miss the point, if anything they’re anti-Saudi which in turns mean that the Shias who join them are likely going to be just a little bit upset at the foreign power that’s been providing arms, training, funding, and implicit legitimacy to the Saudi government for the past several decades. Should this Shia Spring swell to the point where it begins to threaten access to the world’s largest remaining petroleum reserves, the last remaining keystone of American foreign policy in the Middle East could get washed away by another wave of popular dissent.

About a year ago Saudi Prince Turki bin Abdul Aziz al-Saud warned that an uprising will soon begin within Saudi Arabia, correctly hinting that any violence will take the form of internal strife:

Saudi Prince Turki bin Abdul Aziz Al Saud has warned the country’s royal family to step down and flee before a military coup or a popular uprising overthrows the kingdom.

In a letter published by Wagze news agency on Tuesday, the Cairo-based prince warned Saudi Arabia’s ruling family of a fate similar to that of Iraq’s executed dictator Saddam Hussein and the ousted Iranian Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, calling on them to escape before people “cut off our heads in streets.”

He finally warned against a military coup against the ruling family, saying “no one will attack us from outside but our armed forces will attack us.”

As Saudi Arabia begins its own Shia Spring,there’s only one place to look to figure out where the impetus for an uprising came from, the same place the most popular and lucrative form of gambling the world over was born…

It’s not what you have. It’s not what he has. It’s not what he thinks you have. It’s what he thinks you think he has that matters.

Whenever they’re discussing the Iranian threat, military strategists and geopolitical commentators alike are fond of bringing up the fact that it was the Persians who invented chess.

This is meant as something of an analytical catch-all, with all the world a chessboard we are being reminded that Iranians invented the original and timeless game of bold maneuvers, clever feints, and strategic traps. And yet, when you really examine the metaphor, chess really doesn’t fit global interactions all that well.

Everything is in plain view during a chess match: anyone stumbling into a trap was simply too stupid or inexperienced to see what was right in front of them all along. All you have to do to know the strength of your opponent is count the pieces left in play and notice where they lay on the board. Which brings up the fact that unlike conflicts on the world stage, a chess match can only occur between two opponents at a time.

And things take awhile to develop during a chess match, at most you can only loose one piece a turn – there aren’t incredibly risky gambles that can be made which decisively swing the balance of power among numerous opponents in one turn.

That’s not how international affairs really play out. The fact that Iranians invented chess some thousands of years ago really shouldn’t worry us all that much.

It’s notable, but not all that telling. And it certainly shouldn’t worry us as much as another game the ancient Persians invented.

No one’s sure about the details or the exact timeline, but at some point in their imperial past the ancient Persians somehow found the time – around their regular habits of conquering neighboring civilizations, setting the foundations for modern religion, institutionalizing banking, and making vast technological jumps in engineering and science – to invent the game we now call poker.

They called it as-nas back then, or “the ace.” Card games in some form or another likely came into existence in unison with writing, but it was the Persians who created the four suits we still have today and the multi-player game with rounds of successive betting all made based on limited information as some of your opponents cards would be facedown.

Texas may have been a few thousand years off, but given the engrossing simplicity of the game, it’s not too much of a stretch to assume that an early variant of Texas Hold ‘Em existed – which may very well have been called Tehran Hold ‘Em.

So what’s poker have to do with the last decade’s happenings in the Middle East?

Ali Baba had his forty thieves, for Abdul Aziz it was forty servants trying to please.

Unlike the rest of the nations in the Middle East, which almost to a ‘stan were literally drawn into existence within their present borders by the exploitative pens of Empire following the end of World War I, Saudi Arabia’s modern state can be traced back to Abdul Aziz Ibn Saud’s daring nighttime raid over one-hundred years ago.

For generations Aziz’s family, the Saudis, had been consolidating their rule of the Arabian Peninsula under the combined gaze of their vast family fortune and the strict all-encompassing social code espoused by Muhammad Ibn Abdul Wahhab, founder of the Wahhabi sect of Islam.

However Aziz’s father encountered some competition, and had control over the Arabian sands wrested from his grasp by the al-Rashid family, who booted him out of the capital and off to exile in Kuwait. Too old to do anything about the situation, it was up to his son Aziz to return the family to their place at the seat of power in Riyadh.

And so in 1902, twenty-one year-old Abdul Aziz and the forty or-so men with him staged a daring nighttime commando raid on the city of Riyadh: shimmying up a palm tree growing next to the city walls to gain access to it, camel-tying1 several of the city’s inhabitants as they made their way roof-to-roof towards the central square, and then waiting for the Rashidi Governor to make his appearance after morning prayers.

As he appeared in the square, Aziz and his men charged towards him – rifles and daggers drawn, all wailing the traditional Arab battle cry interspersed with shouts of allahu-akbar! This dusty howling dawntime charge of men caught the Rashidi forces completely off-guard, and in the fighting that ensued the Governor was slain and a stunned garrison surrendered to what was actually a vastly outnumbered force of just about forty men.

The elders in Riyadh and across the rest of the Peninsula, accustomed to the rate at which raw-power often makes it a necessity to switch allegiances in tribal societies, quickly returned to stand at the side of the Saudi family. The modern state of Saudi Arabia was born, and there hasn’t yet been cause for them to loose their grip on power.

Until now.

Our present geo-political, –strategic, and –financial situation runs on a set of gears that is precisely calibrated, oftentimes hidden, and growing somewhat rusty even though they’re really quite new. Our geo-financial system is not only the least understood, it’s also the one that America has the least control over and which is the most likely to malfunction.

Very few Americans realize that the Federal Reserve isn’t a part of the United States Government at all, but is actually a conglomerate of private banks. Or that our dollars are based on a fiat system, and not actually tied to gold or any other commodity – although it used to be.

Or that no one, no one at all, is exactly sure why the dollar fluctuates as it does against foreign currencies. You’ll hear plenty of theories about why, but that’s all they are – theories.

The Chinese had tied their yuan to it for a time, but they stopped a few years ago. Industrialized nations the world over hold the dollar as a reserve currency since holding vast amounts of dollars makes buying oil and other commodities cheaper, but some nations want to switch over to the euro or ruble. And no one even knows how many dollars are even out there, as each and every one of them is in fact loaned into existence. Our dollars are not backed by a set amount of gold, or a set amount of anything at all – the Federal Reserve simply agrees to electronically conjure them up as it sees fit.

This is a difficult and paradoxical concept, but here’s an explanation that will help: Imagine that you borrow ten-dollars from your friend Rob, and write him a note saying IOU Ten Bucks. Your friend Mary then needs to borrow ten-dollars, and so you pass the ten-dollar bill you’d gotten from Bob on to her, and she writes you a note saying IOU Ten Bucks.

Now pretend that you or Mary or Bob could walk into almost any store and use the IOU Ten Bucks note instead of a ten-dollar bill to buy some coffee or a book. So if you pretend each IOU Ten Bucks note can be actually used as a ten-dollar bill, there are thirty usable units of currency in circulation even though there’s just one ten-dollar bill.

Well, you don’t have to pretend. Because that’s really what you’re doing every single day.

Every single strip of printed currency is actually an IOU Note, it’s just that the entities that did the lending are enormous, private financial institutions like banks and mortgage companies.2 And chances are you’ve never used printed money to make a purchase of more than one-hundred bucks anyways, the vast majority of our financial interactions are purely electronic. When’s the last time you mailed $250 in cash to Pepco, or put down a down payment of more than $50 on anything?

If all the clients of a bank showed up demanding to cash-out their accounts, no bank in the country would be able to supply them with the cash – because there simply aren’t anywhere near enough real American dollars in the world to cover all of the electronic, loaned, IOU Note, American dollars out there.

Understanding this concept is at the core of understanding the ongoing mortgage and credit crises. If your friends full-names were Fannie Mary and Bob Sterns, all that’s happened is your friend Bob wanted to buy from a store that won’t accept IOU Notes, and has come back for that ten-dollars he originally lent you, so you go to Mary with the IOU Note which she wrote you – but all she has is an IOU Note from someone else since she too lent the ten-dollar bill out.

And that someone also lent the ten-dollar bill out for an IOU Note, so if there are five or six more people down the line the original ten-dollars now represents almost one-hundred IOU Note dollars. Instead of IOU Notes we just have mortgages and car loans.

That’s the simple and inescapable reality at the core of our economic predicament, which just gets more complicated as you substitute nations for individuals, electronic exchanges for written IOU Notes, and more and more layers of lending.

On top of that, there’s the role the American dollars plays as an international currency reserve, since the most industrialized nations want to hold as many dollars or IOU Notes as they can, a kind of inflation sink is created. But there’s one very exposed and brittle gear in the machine our country depends on.

Our present geo-economic system only begin forty-years ago, back when you could supposedly still redeem your printed dollars for a set amount of gold bullion. But then De Gaulle and other heads of state, suspecting we were printing way more dollars than we had gold to back, tried to cash in France’s bucks for gold.

De Gaulle and the rest of the world were right, and so in response the U.S. “closed the gold window” and told the world they were going to just keep on printing out – really, loaning out – dollars as they saw fit.

In response, the world pretty much just shrugged and international financial interactions went along as they had before. There wasn’t really much reason to make much of a fuss, as the most powerful nations in the world had agreed in the Bretton Woods agreement to accept the dollar as the international reserve currency. So in the years since then countless billions of dollars have been loaned into electronic existence across the globe since there was no practical way to replace all of them.

Two other important gears connect to this one: the Carter Doctrine of defending our Gulf oil interests at any cost, and Saudi Arabia’s decision to only allow their oil to be purchased in dollars.

Exactly how big each of these gears is and precisely how they effect each other is impossible to see. There are now uncountable trillions of electronic American dollars in existence across the globe, and no one, including the Saudis themselves, know how much extractable oil is left beneath their sands. The world just knows the dollar is the most important international currency unit, and Saudi Arabia has the largest remaining oil reserves on the planet.

But even though there’s no way to tell how these gears work together, the fact remains that the relationship is there as a vital part of the international economic system, maybe even the most important one. Should Saudi Arabia decide to stop accepting dollars for oil, or even just accept other world currencies, these two gears would be wrenched apart and the economic system we have now would end.

As bad as the current crisis may be, the essential underpinnings of the system have remained intact. The Stock Market has crashed before, that doesn’t mean the entire system will come crashing down with it. Detaching the dollar from Saudi oil would unavoidably cause a much more dire result.

Our American economic machine, which has been leaking and sputtering for several months now, would simply grind to a screeching and violent halt.

Looking at America’s confrontation with Iran like a chess match you see the obvious threats, the potential checkmates: an American naval blockade of Iran or an outright airstrike against Iranian nuclear sites, and Iran’s threat to sink oil tankers in the Strait of Hormuz or launch missiles at America bases in Iraq and at oil facilities across the Gulf. Which is why you should remember that chess doesn’t serve as a good metaphor for geopolitics, and it shouldn’t worry anyone too much that Persians invented the game.

But if the Middle East is one big, brown, sandy poker table – a much more interesting analysis can be made.

There are several players sitting at it. Including America and Iran, there’s also Russia, China, Saudi Arabia, Israel playing each and every pot along with a few smaller more disreputable characters like Hezbollah and Halliburton.

More than just chips in play, occasionally someone will bet blood, bombs, or treasure – the proverbial shirt off their backs – and raise the stakes. The game’s not entirely straight up, sometimes during a hand Iran will lift up one of their hole cards to show Russia, and another to China, but not both to either one and never showing a single card to America or Israel. And sometimes America will chase Iran out of a pot that Israel is also in after Iran re-raises Israel’s initial bet.

Everyone at the table lies constantly about what they have, and just like as in poker, bluffs happen and shows of weakness when there’s really strength are often made, and the most wily players will send their opponents mistells.

And just like in any informal poker game, the rules of play can be shifted around – you can run the cards twice or have prop bets – and it’s not just chips that make their way onto the table.

Here as in the Middle East, the most obvious play isn’t the most likely one. For anyone to assume that Iran’s real intentions are either conventionally against a military they’re vastly outmatched by, or economically against the oil resources their prospective Russian and Chinese allies want intact would mean forgetting that we can’t see Iran’s hole cards.

Geopolitics isn’t chess, no one can see everything that’s on the table. Iran’s best play would not be directly against American interests in the Gulf.

History has an uncanny way of repeating itself. The present Saudi regime was put into power by a decisive raid that lasted all of thirty-minutes. If you have any doubt that the world will be again shifted in a matter of minutes you just have to remember 7/7, JFK, Beirut in 1983, Munich, or 9/11.

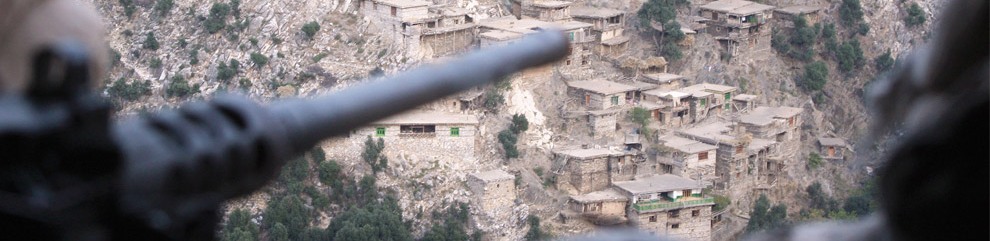

Unconventional, asymmetric attacks lasting only minutes have time and time again altered world events for generations after their occurrence. Depending on the geopolitical context these attacks are sometimes called brilliant military maneuvers and other times terrorism, for an array of reasons that are too complex to get into here.

Iran’s most effective play against America would not be the direct one, but would instead be a much shiftier play. Against a stultified and creaky Saudi regime whose collapse has seemed imminent for the better part of two decades. Either through mass uprising just like the Iranian theocrats came to power themselves, targeted assassinations and bombings, or simply co-opting the government and convincing those in power to turn their backs on their American clients.

The Saudi people see their government as corrupt and immoral, and it’s perceived to be much worse than how the average American believes politicians lie and accept bribes.

Saudi Arabia is built intimately around the idea that its existence is upholding Wahhabism: a stoic and unflinching version of Islam which hacks off thieves’ hands, executes drug-dealers, stones adulterers, requires women to cover all skin except their face, and bans any imaginable form of dissent or religious symbolism.

And yet its leadership is seen by the Saudi people to regularly cavort around in yachts and jets fully stocked with liquor and hookers. Of the hundreds of Saudi princes, very few of them are believed by the Saudi people to live anything close to a life of piety and true submission to God’s will.

Although the Saudis are majority Sunni and the Iranians Shi’a, there’s significant crossover in both nations, and it would be as easy for a worldly Iranian to penetrate Saudi inner-circles as it would be a well-traveled New Yorker to blend into LA. There’s also the fact that the majority of Saudi oil lies beneath desert regions with a majority Shi’a population. Imagining an Iranian program to stir Saudi dissent or to stage a proxy attack against the Saudi government isn’t an exercise in the unlikely or improbable. We may not even see this play occur, as choppy as the international waters are growing, it would be easy to miss a subtle Iranian push beneath the waves.

If Iran sees their region as a poker table, they can see the direct threat of an American military strike. They have threatened to hit back against our oil and strategic interests in the region – so America thinks it knows how Iran will respond if we carry out our threat.

But America would be put in a very tight place indeed and set against highly unfavorable odds should the Iranians find a way to put an end to the dollar’s place as the sole means of payment for Saudi oil. In effect, this decoupling would sweep the chips on the table now onto the floor, and make all the economic advantages we have now meaningless. If this should happen, and there’s growing reason to think things may sheik out this way, if the game gets new rules – blood will be spilled and nothing that occurred leading up to it will matter much at all.

Unlike chess matches, poker games have often ended with the cards cast fluttering to the floor, the table violently upturned, and every fist swinging for the nose of the nearest opponent.

________________________________

–learn more about Tremble the Devil–

1. as a devout Muslim, Aziz would never have been near a pig in his life so would’ve had no idea how to hog-tie.

2. there are still some private ones left at the time of this writing.

Category: Arab Spring, counterinsurgency, economics, islam, news, politics, Saudi Arabia, terrorism | Tags: american foreign policy, civil unrest, financial meltdown, geopolitics, innercity violence, middle east, militant islam, muslim, oil, riots, terrorism, terrorist attacks Comment »