vilest deeds like poison weeds

Heard you might be coming home, just got bail

Wanna go to the mosque, don’t wanna chase tail

It seems I lost my little homie, he’s a changed man

Hit the pen and now no sinnin’ is the game plan

Pools of empty light regularly dot the endless concrete corridors of the Norfolk Prison Colony. They illuminate a lifeless pattern that glows only with the promise of another tomorrow dictated by the clockwork routine of prison life. There’s no warmth found in these pools of light.

But in one of them, you can find hope. At least for fifty-eight minutes out of every hour.

For the other two minutes of each hour Malcolm X waits in his bed while feigning sleep to avoid the regular patrol of the prison guard. Once the guard passes, X slips out of his bed and back into the pool of light cast into his prison cell by an unblinking corridor light, and cracks his book back open.

The first book he reads is the dictionary, he copies down words on its first page and then silently reads them back to himself. This takes Malcolm X the entire night. Then, after months of painstakingly building a vocabulary, he begins to read the works of H.G. Wells, of Gregor Mendel, of Mahatma Gandhi, and of W.E.B. Du Bois. He reads histories, novels, science fiction, and fables. Malcolm X, a man who came of age on the race-divided and crime-rich innercity streets of America, gains his education on the concrete floor of his prison cell. He reads, he learns, and he begins to question.1

And then one day, his brother comes to visit.

i i i

It’s during this visit that Malcolm X is introduced to the religion of Islam. Although this isn’t Islam in its original and authentic form, far from it. The Islam that Malcolm X’s brother brings to him is something of an offshoot, it’s a unique and American sect of Islam that in a way follows the pattern of Mormonism – a unique and American sect of Christianity.

The version of Islam that Malcolm X is brought to has, like Mormonism, its own unique mythology. A mythology that’s wrought with scientific fallacies, historical impossibilities, and genetic absurdities. But what’s more telling is that the beliefs expounded by Christians in the Church of Latter-Day Saints and Muslims in the Nation of Islam are both rooted in a sense of outside persecution. And while persecution for the Mormons came from other Americans who also considered themselves Christians but who resented the Mormons’ cultish secrecy and their leader’s quirky predilection for marrying multiple underage wives, persecution for members of the Nation of Islam came from the Devil himself.

For who but the Devil would’ve trafficked in flesh that was cut off from its native land and then raped so brutally so many millions of times that its own identity was forgotten? Who but the Devil would teach this flesh to hate its own kind – its language, its customs, and the very color of its own skin? Who but the Devil would try to bring that flesh to a religion which taught that God looked nothing like it, but instead that God in fact looked just like the Devil himself? A religion that told that flesh that heaven, escape from its condition, would only come after death while the Devil created its own heaven here on earth from that flesh’s toil?

And who but the Devil himself would keep the poorest and least of that flesh caged behind bars so it would remain deprived, oppressed, and ignorant?1

To Malcolm X, a man who’d grown up in poverty because his father was murdered by white men, been told as a child by a white man that he was a nigger who could never be a lawyer, had white men pull him away from his own black family and place him in white foster care, shined white men’s shoes for nickels as they danced in all-white dances clad in hundred-dollar suits, sold drugs and women to the very same white men who treated him like a social degenerate, whose red hair came from the white slavemaster who’d raped his grandmother, and who’d been put in a cage by white men because the only way he knew to make a living was on the streets – it was an argument that rang with a deafening amount of truth.

And because the Devil is not someone you can live alongside, Malcolm X knew the Devil must be fought. So following his release from prison into the warm early-summer days of 1957, two years after Rosa Parks made way into American legend by refusing to move from her seat on another city bus that forever changed the history of a nation, Malcolm X set out to begin his war against the Devil.

i i i

The years that followed have become strewn with misconceptions and inaccuracies. But the funny thing is, the most misleading statement made about the Civil Rights movement aren’t about the life of Malcolm X.

If there’s one event that captures the way that era has been willfully misrepresented, it would be 1963’s March on Washington. It was during the March on Washington that Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech, words that have become emblematic of the successes of the Civil Rights movement and that have posthumously become King’s final message. The March on Washington is often heralded as a sign of the progress the Civil Rights movement made, and the Speech is conveyed to today’s generations of children as King’s last message to America.

Neither of these assertions are true.

In the years leading up to the March on Washington blacks had staged peaceful sit-ins at segregated restaurants, boycotted bus lines, and blacks and whites alike had been attacked “with fists and iron bars” while staging Freedom Rides that challenged laws against integrated interstate travel. Blacks staging sit-ins were beaten, bombs murdered little black girls attending Sunday school, buses full of Freedom Riders were set afire, and the federal government “watched, took notes, did nothing.”2

In the early 1960s “black people rose in rebellion all over the South” and it seemed that “revolt was always minutes away, in a timing mechanism which no one had set, but which might go off with some unpredictable set of events.”3 It was in this heady and volatile mixture of racial tension and youthful idealism that a spontaneous plan emerged among groups of blacks to get to Washington “any way they could – in rickety old cars, on buses, hitch-hiking – walking, even, if they had to”4 and then march “on Washington, march on the Senate, march on the White House, march on the Congress, and tie it up, bring it to a halt, not let the government proceed.”5 It was to be “a national bitterness; militant, unorganized, and leaderless” that would be undertaken by those who were “sick and tired of the black man’s neck under the white man’s heel.”6

But that’s not what it was at all. When the white establishment learned of the angry black wave which was beginning to ripple across the nation towards the shores of Washington, they enacted an ingenious plan to counter it – they became a part of it, and welcomed it.

The white establishment knew this would be possible because the New York Times had reported that the main civil rights organizations were all scrambling for donations, each attempting to elbow the other away from the potential donors who were in short supply. The NAACP especially felt that since whenever another organization put on a highly publicized demonstration that drew in large crowds and a large influx of money, it should be given a share of the money since it ended up bailing many of the other organization’s jailed protesters out of jail and representing them in court.7

These financial fissure points were filled with a highly publicized white donation to the “big six,” the leaders of the various Civil Rights groups who were looked to by blacks to dictate the terms of the March on Washington, in return for being allowed to add four white members to their group and create a “big ten.” Media coverage implied that it would be this “big ten” who would “supervise” the “mood” and “direction” of the March on Washington. The Kennedy administration, fearful of the massive potential for unrest in the nation’s capital, gave its tacit approval to the “big ten” and made it seem democratic for Americans to join the March.8

i i i

Soon the middle and upper class blacks who had at first deplored what they perceived as a poor black March joined the tide, as did the whites who joined the March on Washington as it became a chic status-symbol, became a Kentucky Derby but with a bunch of negroes running around instead of horses. As a result, the March on Washington, in the words of Malcolm X, “lost its militancy.”

“It ceased to be angry, it ceased to be hot, it ceased to be uncompromising. Why, it even ceased to be a march. It became a picnic.”9 The March became so tightly controlled that the blacks who came were instructed “what time to hit town, where to stop, what signs to carry, what song to sing, what speech they could make, and what speech they couldn’t make, and then told them to get out of town by sundown.”10

Which is just what the blacks did, never laying down across the plush lawns and even runways of Washington and refusing to budge until concrete Civil Rights legislation was passed but instead coming and going in the light of just one day. A March intended to embody the heated black anger which had been stoked in the furnace of white discrimination, white beatings, white segregation, and white bombs instead became a “gentle flood” of integration that had been told “how to arrive, when, where to arrive, where to assemble, when to start marching, the route to march.”11

And it’s telling that it was in this context that Dr. Martin Luther King gave what is far and away his most famous speech, and in the process created what’s been preserved as the most compelling image of the Civil Rights era: standing at a podium framed by the Lincoln Memorial in front of a sea of peaceful and biracial faces, a quarter-million deep, that blanked the National Mall.

Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech has been recited and memorized by generations of school children and is easily the most celebrated text of the Civil Rights era. But it was given at an event that presented an image of America that had been bought, one that was a lie. Much like the title in front of Dr. King’s name is a lie, and our perception of his character as a godly and moral man is a lie – Martin Luther King Jr. was a prodigious womanizer who cheated on the woman who had borne his children dozens and dozens of times. Even King himself let his dream go and did not carry it to his grave, his final message was a drastically different one.

But we don’t want to remember this, we willfully choose to remember Dr. Martin Luther King as having a wonderful dream that we’re moving closer to each and every day, and to preserve him as the greatest man who lived in the Civil Rights era. And the March on Washington is remembered as one of the great triumphs of the Civil Rights movement, when in fact it was a farce that undermined the true goal of the blacks who started it.

It’s so much easier to accept things as they’re presented to us.

We forget the reality of King’s life and the reality of the context his dream was created in, the March, just as we forget that in the years following his speech America moved farther than ever from the image he presented in it. In the years that followed the March on Washington there were outbreaks of black violence in nearly every part of the country. Out and out riots occurred in Rochester, Jersey City, Chicago, Philadelphia, and numerous other cities.

Stores were looted and firebombed, policemen and National Guardsmen responded to the violence that stretched from coast to coast. By the summer of 1966 looting and fire-bombing in Chicago led to the shooting deaths of a thirteen-year-old boy and a pregnant fourteen-year-old girl by authorities, in Cleveland four blacks were shot after a “commotion.” Then in the summer of ’67 came “the greatest urban riots of American history.” Blacks attacked not only whites themselves, but every local symbol of white society they could get their once-shackled hands on. The National Advisory Commission on Urban Disorders reported eight major uprisings, thirty-three “serious but not major” outbreaks of violence, and 123 smaller riots. Eighty-three civilians, most of them black, died as a result of the violence.12

If there ever needs to be a final ruling on whether Malcolm X or Martin Luther King Jr. better embodied and eloquated the black experience of the ’60s and ’70s, it can be found in the anger and destruction of these years. In the reality of their origins, your average African-American from that era shared much more with X’s impoverished and tumultuous upbringing than with King’s privileged and peaceful one.

And so it was Malcolm X who served as the best and most prominent spokesman for Black Power – a call to pride and independence for blacks.

i i i

As Malcolm X put it, “you’ll get your freedom by letting your enemy know you’ll do anything to get your freedom; then you’ll get it. When you get that kind of attitude… they’ll call you a ‘crazy nigger’ …or they’ll call you an extremist or a subversive, or seditious, or a red or a radical. But when you stay radical long enough and get enough people to be like you, you’ll get your freedom.” Malcolm X reminded his followers that “you came here on a slave ship. In chains, like a horse, or a cow, or a chicken,” and that “America’s problem is us. We’re her problem. The only reason she has a problem is that she doesn’t want us here.”

While King dreamed of peaceful racial integration, X saw the reality and necessity of violent action against an oppressive white establishment – “a common oppressor, a common exploiter, and a common discriminator.” Malcolm X argued that “any time you live in a society supposedly based upon law, and it doesn’t enforce its own law because the color of a man’s skin happens to be wrong, then I say these people are justified to resort to any means necessary to bring about justice where the government can’t give them justice.”13 And he taught that “once we all realize that we have a common enemy, then we unite – on the basis of what we have in common. And what we have foremost in common is that enemy – the white man.”

As a member of the Nation of Islam it was widely said that Malcolm X was the only man in America who “could stop a race riot – or start one.” X had a “ghetto instinct,” could feel the level of tension in a ghetto audience, could understand its language.14 And he could speak in a language which they understood, a fact well-illustrated as the coming decade played out and urban black America began to revolt against what it saw as an oppressive and unjust white establishment.

As the revolutionary decade of the 1960’s found its stride, urban violence in America grew to new heights. Police were regularly acquitted for killing innocent black students, shooting black rioters in the back, and cases that captured the racist injustice of the time came “randomly but persistently out of a racism deep in the institutions, the mind of the country.”15 Polls showed that nearly half of America’s blacks under the age of twenty-one had great respect for the militant Black Panther Party, and despite some attempts by the white establishment to integrate blacks and provide economic incentives to them the unemployment, crime, drug addiction, and violence that was destroying the black lower class only continued to grow in force.

Almost fifteen years after the March on Washington, the unemployment rate among black youth had risen to just under thirty-five percent, and blacks were seven times more likely to die of homicide than whites. The next year the New York Times reported on the American racial divide: “the places that experienced urban riots in the 1960’s have, with a few exceptions, changed little, and the conditions of poverty have spread in most cities.”16

And then – gradually at first, but soon gaining the silent and unstoppable momentum of a giant gear that’s nudged into ever-building motion – the system began to respond.

i i i

In one of the more ironic statements in the history of the American Presidency, while running for office in the summer of ’68 Richard Nixon declared that there needed to be a new respect for the law in the USA, that there should be “a new determination that when a man disobeys the law, he pays the penalty for his crime.”17 This statement was tacitly aimed at the black rioters who were violently protesting across thousands and thousands of miles of inner-city American streets that summer, rising in what was beginning to seem like an inevitable racial insurrection during the long hot summers of the 1960s.

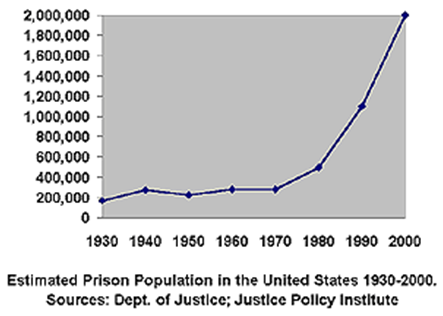

Up until 1970, a year into Richard Nixon’s presidency, the American prison population had been remarkably stable and on-par with other Western democracies – at about one-tenth of one-percent of the population. But then, “at a moment in U.S. history when the Civil Rights movement had faltered,” the population of our prison system began to climb.18

The same hopelessness and poverty which were fueling the race riots stoked addiction, crime, and violence in America’s inner-cities. And it was addiction, which spun off to cause so much ancillary crime and violence, that Nixon was nominally attempting to combat when he declared a War on Drugs.

The popularly cited motivation for the War on Drugs is that it was a response to the growing numbers of military serviceman who were getting hooked on heroin and other narcotics while serving in the Vietnam War. Although that was a troublesome issue, when you know the reality of all past American drugs laws it quickly becomes apparent that there’s no way in hell that was the only impetus behind this wave of anti-drug legislation, and that Nixon was using soldiers’ addiction as opportunistic displacement.

Following the Civil War the earliest anti-drug laws were passed in some states, banning the consumption of alcohol. Not, of course, for everyone.

Whites could drink as much as they pleased, but if you were a minority in much of antebellum America you were prohibited from imbibing at all.

i i i

At the time it was a widely held belief in American politics that some races, bless their brown souls, simply couldn’t control themselves. Furthering the codification of this perception, in 1901 Henry Cabot Lodge spearheaded a law in the U.S. Senate banning the sale of liquor and now opiates as well to all “uncivilized races.”

In this case, “uncivilized” was synonymous with “dark.” At this point in American history, whites could get as drunk, high, or smacked as they wanted – while the brown-skinned members of American society were completely banned from consuming any intoxicant. Throughout the first half of the 20th Century, any violence carried out by a black man against a white could be attributed to the commonly-held caricature of a “cocaine-crazed negro.” Newspaper headlines screamed of coked-up black criminals who were SHOT BUT DON’T DIE!, and policemen claiming that WE NEED BIGGER BULLETS! because their current caliber wasn’t large enough to stop the crack-crazed negroes they routinely came up against in the line of duty.

However blacks weren’t singled out as a racial minority, the first anti-marijuana laws targeted the wave of Mexican immigrants who were spreading across the American South. They were seen, then as now, to be stealing jobs and government resources from resident whites, and so politicians from that region of the country first banned marijuana use by minorities alone, and then eventually altogether.

Leading up to Nixon’s War on Drugs, each and every drug law passed was inextricably bound to racial prejudice. In other words, “all of our drug laws have originally been based on racism… all of these laws are based on the belief that there is a class in society that can control themselves, and there is a class in society which cannot.”19

Nixon’s public claim that the War on Drugs was primarily a response to the growing number of addicted veterans was at best a lie of omission. Taking into account past legal precedent, and the fact that American urban centers were being wracked by a series of seemingly unending race riots, it becomes self-evident that the War on Drugs was simply another page in a story of American anti-drug laws that has always been rooted in racism.

Then in 1973, with Nixon desperately attempting to spin his way out of Watergate, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller passed a set of laws that were soon mimicked by several other states and then finally the entire federal government.

They were minimum sentencing laws for drug crimes that, in part because they included a fifteen-year prison term equivalent to what you’d get for second-degree murder for possessing even a small amount of narcotics, were the harshest the country had ever seen. The per-capita prison population of the United States remained constant from 1930 to right around 1973, at which point the graph begins an exponential climb that grows steeper and steeper with every passing year.

These counter-narcotics laws that, both by design and in practice, fueled an explosion in our prison population – a population which started disproportionately black – with 90% of those incarcerated under the Rockefeller laws either Latino or black – and only growing to become more so as the years passed. Between 1979 and 1990 blacks made up a steady percent of our overall population, but between those same years blacks went from making up 39% of our drug-related prison population to 53% of it.20

Today that number’s down to 51.2%. An improvement, but hardly.

Through the 1980s this disparate growth was fueled by the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, one of the hundreds of crime bills passed by state and Congressional legislatures in the 1980s and 1990s. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act imposed the first of the mandatory minimum sentencing laws, here five-years in prison without chance of parole for anyone caught selling a substantial-enough amount of heroin, methamphetamine, marijuana, or cocaine. This last drug, cocaine, had a unique provision.

You’d receive the same unparolable five-year sentence for selling either 5 grams of crack cocaine as you would selling one-hundred times that much – 500 grams – of powder cocaine. Crack and powder cocaine are pharmacologically the exact same drug, there’re only two important differences. One is that crack cocaine is smoked while powder cocaine is snorted. The other is a bit more telling. Powder cocaine was mainly consumed by whites, whereas crack cocaine was the form of choice for innercity blacks.

Critics, for good reason, blasted the law as shamelessly racist.21

America introduced a solution to civil disorder and social injustice that wasn’t novel, it’s simply grown to become unmatched in scale. By 2003, the percentage of our population in prison dwarfed England’s level, our international neighbor whose culture and mores are closest to ours. We have, proportionally, six-times our population locked up behind bars as our tea-sipping crumpet-munching cousins across the pond. For France and Germany, the difference approaches ten-times as many.

Our prison population has increased five-fold in just thirty years. In terms of the global population, we have just 5% of that but fully a quarter of the world’s prisoners.22 And these American prisoners have one common and inescapable denominator that you’ve almost certainly already stereotyped them with – but for good reason. The stereotype of the black male American prisoner is, among other things, an accurate reflection of reality.

Although only about 12% of the American population is black, over a third of the two-million Americans locked up in prison are black. And despite the fact that only 14% of all illicit drug users are black, blacks make up over half of those in prison for drug offenses. A black man is eight-times as likely as a white man to be locked up at some point in his life. At any one time in America, almost a third of black American males in their twenties are under some form of “correctional supervision” – if not actually incarcerated, then either on probation or on parole, meaning they’ve recently passed through the American penal system.23

This means that as of 1996, a sixteen-year-old kid in America would have nearly a one-in-three chance of spending some time behind bars if he was unlucky enough to have been born black. If he happened to be born white, he’d only face a 4% chance of incarceration – a disparity that’s been steadily increasing since then. In Chicago’s home state there’re 10,000 more black prisoners than black college students, and for every two black students enrolled in college there are five elsewhere in the state either locked up or on parole.24

In 2001 a government survey revealed that the per-capita rate of illicit drug use was only point-two of a percent higher for blacks, and yet three-quarters of those arrested for drug possession were black. Nearly half of all drug arrests in America are for simple marijuana offenses. These statistical realities should do much more than stagger you.

If you’re black – they terrify you.

i i i

Throughout history, social uprising have coincided with high levels of economic disparity. The American Revolution, the French Revolution, China’s Cultural Revolution, both of Russia’s modern revolutions, and even the ’79 Iranian Revolution all received a heavy push from economic discontent. It seems as if the poor have some unseen threshold, like they can only get so poor before they lash out violently against the system. Like the odds a social uprising will occur increases in tandem with the level of economic disparity.

And for going on two generations now, America’s level of economic disparity has been steadily rising. This ongoing financial crisis may be what finally causes it to crest over. The fact that black males now have twice the unemployment rate of white males barely even begins to explore the issue.

The precise era that saw a drug-law fueled explosion in our prison population, the early 1970s, are the exact same years that the economic situation of blacks began to starkly worsen and that the gap between rich and poor is wrenched wide open. Beginning in those years and continuing into today, “the economic status of black compared to that of whites has, on average, stagnated or deteriorated.”25 Up until 1973, the precise year the Rockefeller drug laws were passed, the difference between black and white median income had been closing. But then that year it changed course, and in “an ominous bellwether… the gap between black and white incomes started to grow wider again, in both absolute and relative terms.”26

In the nearly forty years since America’s modern drug laws were passed, there has been a massive increase in economic inequality by any measure. In the early 1970’s not only did the income gap between black and white begin to widen again, it also becomes much more top-heavily favored to the very rich – who happen to be almost exclusively white as well.

One way to capture it is by examining what portion of America’s total income the top 1% of earners receive. The share of that top 1% has nearly doubled since 1970, and it’s now the same size as the income earned by everyone in the bottom 40% of earners combined.27

So the very few families who make up the top 1% of all earners have a combined income that matches the incomes of all the families in the bottom 40% of earners.

Looking at economic well-being another way, in terms of financial wealth or “stocks, bonds, real estate, businesses, and other financial instruments,” as of 1998 the top 1% of families controlled nearly half of that pie, with the top 20% controlling fully 93% of it. Meanwhile, the bottom 40% of families actually have negative financial wealth – their debts actually surpass their assets.28

And this cavernous gap has only been widening, between 1998 and 2001 the net worth of families in the top 10% of America jumped 69%, significantly more than any other group.29 In the years leading up to that point, between 1988 and 1999, the difference in net worth between black families and white families grew by $16,000 and the gap in net financial assets grew by $20,000. By 2004 white families had an average net worth of $81,000, and black families an average net worth of just $8,000 – roughly a tenth the average white family’s.30

With home equity making up 44% of an average American’s family’s net worth and fully 60% among our middle class,31 the statistics around homeownernship further delineate the racial schisms of American wealth. Not only do blacks pay higher interest rates, have higher downpayments, have less access to credit, get turned down more frequently for loans no matter what’s controlled for, and pay what amounts to an 18% “segregation tax” because homes in black neighborhoods have much less equity than homes in white neighborhoods32 – but since 1970 black homes have appreciated in value roughly half as much as white homes.33 And as the real estate market has crashed blacks have suffered much more severely than whites. As it was stated earlier, even when income and credit are controlled for black families now have their homes foreclosed on and are thrown out into the street three-times as often as white families.

Exactly what impact modern drugs laws had on this growing level of racial economic disparity is impossible to know, however it seems more than a little suspicious that so many economic factors line up so well with the passage of our modern drug laws and the incredibly disproportionate number of blacks who were thrown into prison.

But one thing that’s not tough to figure out, is whether being exposed to the American penal system increases or decreases someone’s propensity for violence.

i i i

Getting a man to kill someone right in front of them is surprisingly tough to do. The US Army didn’t get the formula right until Vietnam, when it combined the modern psychological principles of classic and operant conditioning, along with heavy doses of desensitization to violence and the appropriate levels of cultural and moral distance.

Our modern prisons, while not using classic or operant conditioning, appear to be reaching the same ends. Not only does increased incarceration raise the rate of violent crimes at the community level,34 but sticking someone in jail desensitizes them to violence and increases their level of cultural, moral, and social distance from anyone not in their own race.

No where in the modern world is someone more forced to “practice thinking of a particular class as less than human in a socially stratified environment,” a crucial step in becoming prepared to take someone’s life.35 It is impossible to survive in most prisons without at least loosely aligning yourself with whatever gang your race corresponds to, and steering well clear anything beyond cursory or institutionally-forced interaction with members of another race.

Although America’s five-fold per-capita increase in the incarceration rate hasn’t seemed to have increased the overall level of violent crime, a study released in 2002 revealed that without the advances in medical technology that we’ve made since 1970 the murder rate would be between three and four times higher than it is today.36

Numbers aside, there’s absolutely no way spending time in prison pacifies someone. And upon their release, prisoners often become ineligible for public housing and are denied welfare. So getting a job and trying to find a legitimate way to support themselves is far from easy for ex-cons, more often then not they feel forced to go back to a life of crime to support themselves and any family they might have.

Unemployment rates as high as fifty-percent are frequently cited by those who have researched and followed the lives of former prisoners. One recent study put the unemployment rate at 60% in the first year after release, and another survey found that two-thirds of the employers surveyed in five large cities would never hire an ex-con.37 Having to state that you’ve been incarcerated on your job application means that any jobs beyond the most menial and low-paying will likely remain out-of-reach. And in today’s turbulent economic times, when even those with advanced college degrees have trouble finding any kind of paid work, the prospect for an ex-con is even more grim.

Due to the incredibly high concentration of blacks in the American prison population, the hope-numbing impact of being held in prison and then being hard-pressed to find employment afterward enforces “the stigma of race [that] remains the unmeltable condition of the black social and economic situation.”38

Racism is generally understood in America to have fallen to an all-time low. But this is an illusion, created because our prisons and the hundreds of thousands of black men inside of them are built at sites unseen. A “subtler and more covert” racism has been enabled as prison populations artificially bend racially specific underemployment rates as “mass incarceration makes it easier for the majority culture to continue to ignore the urban ghettos that live on beneath official rhetoric.”39

The Civil Rights movement was marked by dozens and dozens of indelible images of racism that were carried in the media each day – black children being marched past an angry white mob into a newly segregated school, police dogs being sicced on peaceful black protesters, burnt-out remains of bombed black churches, one black man behind a pulpit preaching of Christian love and patience and another black man punctuating with his fist the need for angry black action, crowds full of college students both black and white being sprayed at times by firehoses and other times by bullets.

We’ve all seen the living, breathing, killing reality of racism in the 1970s. None of us now are able to see its existence now, because racism no longer lives on the front pages of our newspapers and during our evening news – instead it’s been suffocated inside poured concrete walls which rise and fall in invisible existence, locked safely out of sight.

Until from the barrel of a terrorist’s gun poured a breathe that brought it back to life for all of us.